I really dread that question.

Whenever someone asks me that, it’s generally after I’ve talked their heads off about my tiny trees. Generally I’ll shrug and mention “The Dinner Game,” an excellent movie in which the protagonist invites obsessive idiots to a dinner party. The antagonist has binders of photos of miniature landmarks that he’s recreated using only glue and toothpick sticks.

I mention that I would be an excellent idiot.

That’s usually the end of it, but I’ve decided it’s an important question to answer. To do that I’m going to need to discuss some math. Don’t worry, we’ll be focussing on the big picture rather than any equations. The relevance will make sense soon.

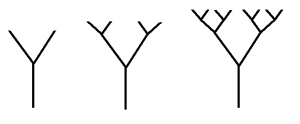

Fractals are mathematical sets that exhibit a repeating pattern that is visible at every scale. Like this:

This is Sierpinski’s triangle. Looks complex right? Well, it can be built pretty simply.

Build a Pascal’s triangle, shade the even numbers and there you go. All of a sudden a very complex pattern has emerged from simple ‘rules.’ Fine then, what do these triangles have to do with bonsai? I’m glad you asked. Let’s look at some more simple fractals, some that might be more relevant.

Ehh? Ehhhhhh!? All of a sudden you can see that these shapes might look relevant to very boring trees. Change the ‘rules’ that generate your tree and you start to see some more interesting shapes.

Fractals are natural shapes. The more you look into nature, the more you find them.

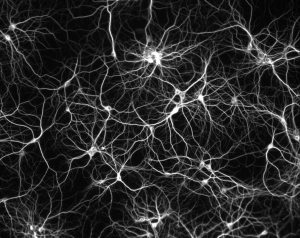

In the hippocampus,

the anatomy of the lungs,

the veins of a leaf,

or the branches of the trunk and trees itself. Whatever language life has, whatever logic or description of it as a whole is found in this sort of math. They have a curious kind of beauty in natural systems absent from the garish posters found in pretty much every dorm room. You know.

Ungh. Whatever.

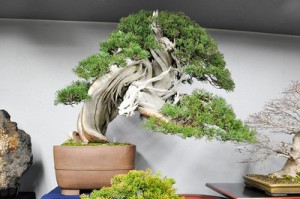

It’s easy to start to see these sorts of patterns in bonsai, particularly great bonsai.

If you notice though, none of these trees resemble the perfect mathematical trees that we depicted above. Instead they depict disturbed patterns, the trees’ internal logic bent by whatever adversities or unique situations that nature inflicted upon them. Even still, despite this adversity the tree pushes on, reproducing, flowering, growing, insisting upon its internal logic, its own rightness.

The fractal pattern of good bonsai means that the bonsai artist does not simply tell a story, they tell a story using that internal mathematic language of life, articulated in a living organism. Bonsai then is not simply visual art, it is performance art, spoken between the tree and the artist in the same language that guides all manner of natural system.

That is why I bonsai.

Very excited to read your bonsai adventures and lessons. Thanks for taking the time to do a blog!

LikeLike

Hey my first comment! Thanks so much for reading, really appreciate having an audience.

LikeLike

More please.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Coming soon! I gotta style a big Japanese maple. Will post pics and talk about fractals and their relationship to the techniques of bonsai. :]

Or at least, my thoughts on them.

LikeLike

What a clever way to explain about bonsai. I am very bad in mathematics, it may explain the looks of my bonsai collection 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is a thoughtful and interesting post. I am in a similar zone and I am just about to embark on my first Japanese maple as soon as pruning season arrives. I will definitely check back for updates.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Japanese maples do great for me here! Hungry little trees that just grow and grow and grow. What Walter and Jim have said to me about pruning is that you can cut any time of the year. Wiring though you should reserve for just before they leaf out in March.

LikeLike

Yes! Branch ramification is a fractal and they are self similar. Lingnan penjing principle says when a branch is cut, its structure should look like another penjing, a self-similarity. Besides the often mentioned Fibonacci number, golden proportion etc., bonsai, like all natural things, manifests in mathematical concepts. In China penjing is also based on the Daoist Taiji (Taichi) philosophical concept: out of primordial nothing came one; one divides into two, a Ying and a Yang; two develops into four phases (such as north, south, east, west, the four seasons etc.); four became eight (such as Yijing’s eight trigrams for fortune telling); it goes on dividing into all things (wanwu) in this world. In Taiwan, branch ramification is also called a taichi branch development method.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Mr. C!

I had no idea that you had a blog! I even reblogged one of your articles before I knew it was you! It’s hard to believe that Lingnan penjing already had references to self similarity, but it makes sense. I’d love it if you could write more on the Chinese philosophy behind bonsai – unfortunately, I’m much more familiar with Japanese trees than Chinese, but I’m always hungry for more knowledge. Will be eagerly following your blog!

Joe

LikeLike

Happy New Year! I hope to write something about Lingnan penjing and other Chinese schools of penjing. They are rooted in arts, philosophies and regional ways of life. Your reply to the old Japanese postcards prompted me to write a new blog on the ever changing aesthetics in bonsai. This time, I boldly suggested the asymmetric triangular display, so prevalent in many bonsai shows today, may be a revival of an ancient art. A blasphemy to the traditionalists.

Best wishes to your evolution research.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Love this. Read the other posts too. Can’t wait to see more posts in the future. Throw a link on reddit whenever you update this please 🙂

LikeLike

Thanks man! Will leave a link on reddit, but man, I feel like a shill kind of. Oh well. Onwards and upwards.

LikeLike

Great work Joe. I’m very glad you are doing this.

The same math applies to music as well. When I play slide guitar, I tune the instrument to an open chord, meaning that all of the vibrations between the strings are sympathetic. Some players use concert tuning to play slide and work to keep the other strings muted when the slide touches the strings because they sound harsh and atonal if they are heard. With an open chord though, all the vibrations resonate with one another and any contact the slide makes produces sympathetic vibrations, literally good vibrations.

I use this to my advantage playing all the time – I have to do less actual work to make more sound. I can’t tell you precisely what notes I just played, I just know they fit that particular musical moment.

Keith Richards says he doesn’t write songs so much as he receives them. Gary Bartz says the only time he really improvises is when he makes a mistake, and has to think off the top if his head to get back to where he can rely on his ears being open to follow the music he is hearing.

I think I am able to approach bonsai the same way now too. Whatever the art, an approach that promotes creativity, fun, and working to see (or hear) what naturally comes next is the kind of artistic foundation that makes sense to me. Whether you are James Brown fining the drummer for missing the off-beat, or the bonsai fundamentalist sensei that makes you wire an Easter White Cedar so it looks like a Hynoki, you are not really making honest art. I wouldn’t want to be in either band.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hey Tom!

Thanks for the kind words, really appreciate you taking the time to respond and read through my BS. I’ll be honest, I’m completely ignorant when it comes to music. I heard someone say that “intuition is knowing something without knowing how you know it.” That’s stuck with me for a long time, and it seems to kind of speak to your methodology. My guess is that your brain is figuring out all of the math involved without you even having to think of it, same as you do with your bonsai. Will you be coming down in March? I’m going stir crazy over here, I can’t do any work on any trees because they’re all under the snow!

Joe

LikeLike