First, some preamble: I am not religious. I say that not to invite readers into the interminable debate between religion and atheism, but to give some context to my appreciation for one of my favorite thinkers, Kierkegaard (from now on K. As a side note, I will intersperse pictures of my summer, just so that this is not one long drawn out essay).

New benches!

I first encountered K. as a teenager, drunk on the heady writings of Nietzsche and Sartre, in love with Camus and eager to read more like them. I first read his contemplation of Abraham and did not realize the full weight it would have on my thinking and my life. I was turned off by his religiosity, but, really, unable to get past it. Because K.’s writings are not simply for the religious.

In college I started taking formal classes in philosophy – it is what led me to a career in science, finally an opportunity to enact put my philosophy to use in some way. I became obsessed with K., reading him continuously, obnoxiously discussing him with my beautiful girlfriend in cafes to the sneering dismay of other patrons. I must have appeared quite the pretentious shit bag. Eventually I even traveled to Denmark to study K. before writing a well received, if controversial, thesis about his relationship to Socrates.

Flowers, and some nutrient deficiency.

K.’s meditation on Abraham is important. To philosophy, to modern conceptions of Christianity and most importantly for our purposes, to me. A refresher: Abraham for some decades was unable to conceive a son, promised in the covenant made with God. Finally it is given to him when he is ninety nine years old. One wonders how this was possible without viagra.

Despite the deliverance of his son, Isaac, Abe is commanded by God to take him onto Mount Moriah, bind his wrists and sacrifice his son. It was a three day walk, with Isaac carrying the wood he would be sacrificed upon. For me this is a comfortable story when it is viewed through the lens of distance. Three thousand years and the amount of mythic stories in the Bible, talking snakes, worldwide floods, it’s easy to dismiss this as another outlandish story, especially given the elements of Isaac’s conception.

K. demands us to understand the story differently, he orders us to contemplate that walk, taking a beloved child up the mountain, knowing that God has ordered you to stab him in the chest and watch his blood trickle down a wooden stake, into the sandy earth. Really imagine that.

One recoils.

Far from being the staid patriarch of Christianity, when viewed in a contemporary lens, as a person who is hearing the voice of God(?) and taking his son up onto a mountain to stab him to death, Abraham appears to be a lunatic. Externally he has more in common with the nut jobs that flew those planes into the buildings.

Abraham has done away with everything, he is disintegrating his family, sacrificing all that was promised to him by God and becoming a monster. Abraham has done this all because he is answering the internal call of God. God does not appear to him as a burning bush, letters in the sky, etc., he is simply a voice. Abraham does not question if this is a djinni or Satan himself (seems like his bag really).

This was a huge problem for me. Why didn’t he test it? Why didn’t he ask for a sign? How could he throw everything away on one internal command?

Because you cannot be wrong about the word of God, and, once hearing it you can either choose to take a leap of faith or not. It is likened to being in love, it is an internal state, inspired perhaps by external events, but entirely internal. K. wrote on love before: perhaps inspired by his broken off wedding, he penned The Seducer’s Diary, a story in which Cordelia confesses her love in language remarkably similar to that he describes Abraham with. In this story she has been moved to love, but has no external object to hook it onto; Johannes is a quite insufficient scoundrel.

By virtue of the absurd, Abraham has been moved to a new relationship with his son. He gets his son back, an angel stops the plunging dagger and Abraham gets everything back by virtue of the absurd. Whether it is in a romantic relationship or a paternal one, the absurdity of following irrational, blindingly stupid, contradictory and self defeating goals is improved and returned to the person who takes the leap and obeys their own internal edict.

I dropped out of my PhD program.

It wasn’t working for me. I wasn’t interested in the work particularly, I dreaded spending twelve hours and change in front of the lab bench on weekends, daily I contemplated driving my Honda accord into a telephone post at 20 mph, not to hurt myself, but just because dealing with an accident would be better than working.

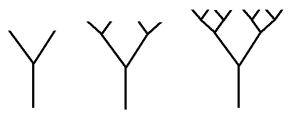

When I am very quiet, when I look into myself, when I sit in my garden I only hear one command: Make beautiful trees.

It’s so simple. Blindingly so. I didn’t even dare to dream it, dare to talk about it, until two of my professors, my girlfriend and the radio show host Elvis Durand all suggested following my dreams, abandoning the career I’m happening in and listening to that voice. It doesn’t make any sense. There’s very little money in bonsai, it’s a niche market and a discipline that takes a tremendous amount of knowledge, hard work, manual labor and possibly a stint abroad studying with a master.

I quickly found work in a private bonsai collection and spend my days working with artists to maintain upwards of 1000 imported trees. I don’t know where this road leads. When I think rationally, I think that this is a very silly move, doomed to end in failure. But there’s still that little voice, persistent, always whispering, waiting for a pause in life that tells me what I’m really here to do is make beautiful trees.

I feel a singularity of purpose that I’ve not felt in a long time, and, at the same time a deep humility. Working with professional I recognize how much a gap exists between my praxis and their’s. There’s an incredible craft that goes into simply maintaining 1000 bonsai trees instead of 40 and, to my chagrin, I’ve found that I cannot even water properly.

If Abraham can stab his son, I can learn. I can figure out some way to satisfy that quiet, ever present voice. Let’s see how this goes.

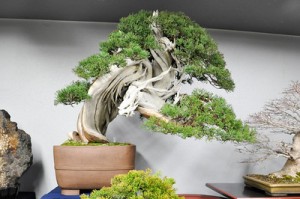

Selected as one of the 25 Exceptional Trees Award in the 2013 World Bonsai Friendship Federation Photo Contest.

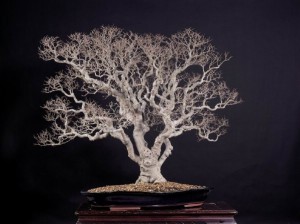

Selected as one of the 25 Exceptional Trees Award in the 2013 World Bonsai Friendship Federation Photo Contest.

The painter here simply did not know how to convincingly trick the eye into perceiving space.

The painter here simply did not know how to convincingly trick the eye into perceiving space.